80 Years After Hiroshima: Why It Still Matters

- Sep 15, 2025

- 5 min read

By Hannah Kent

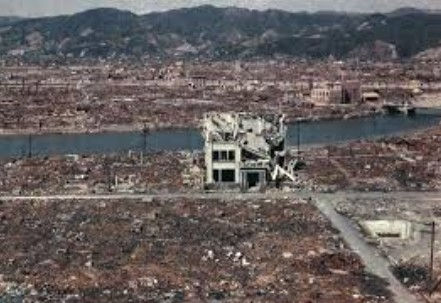

On August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m., the United States dropped the world's first atomic weapon to be used in war in Hiroshima, Japan. Within seconds, the uranium bomb, known by the codename ‘Little Boy’, destroyed over two-thirds of the city, exploding with the force of approximately 15 kilotons of TNT. A dazzling light covered the sky, and a blast of scorching heat vaporised many individuals close to the epicentre in an instant. As recalled by survivor Shigeko Sasamori,

"My clothes were burned away. My skin was hanging. I was no longer human."

Around 70,000 civilians were instantly killed in the initial blast, and by December 1945, around 70,000 more had been killed in total, primarily due to Acute Radiation Sickness (ARS) and burns. Thousands more would eventually die over the coming years from cancers, leukaemia, and genetic mutations that afflicted unborn, innocent generations. Just three days later, on August 9, a second, more powerful plutonium bomb called ‘Fat Man’ was dropped on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 70,000 people by the year’s end. For reference, if a bomb the same size and power as ‘Little Boy’ were dropped on Loreto, there would be around 13,000 fatalities, and 44,000 injured; however, Normanhurst is much less densely packed than Hiroshima, and these numbers do not account for the residual effects. Hiroshima remains the only time nuclear weapons have been used in war to this date, 80 years later.

Would you be injured if a bomb were dropped on Loreto?

The bombings ended World War II, but at an immense human cost. Historians continue to debate the necessity and morality of the attacks, and this debate is central to why Hiroshima still matters today. The traditional perspective, represented by American historian Richard B. Frank, holds that the bombings brought about Japan's surrender and averted an invasion (known as Operation Downfall), which the Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated would exact up to 500,000 American casualties and millions of Japanese. In his book Downfall (1999), Frank concludes that "without the atomic bombings, the war would have dragged on at staggering cost.".

Other historians, however, contest this. American historian and political economist, Gar Alperovitz, in his book Atomic Diplomacy (1965), suggested that Japan was already on the verge of surrender, its navy destroyed, its air force shattered, and its cities laid waste by months of conventional firebombing. "Japan was already beaten,". U.S. General and the 34th President of the United States, Dwight Eisenhower, reflected that, " the dropping of the bomb was completely unnecessary." Revisionists, however, point to the Soviet Union's entry into the war on August 8 as the main reason for Japan’s surrender, not the bomb. Since Tokyo would prefer to be bombed by the Americans than to be overrun by communists. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, through his book Racing the Enemy (2005), makes this point most forcefully; "It was the Soviet entry into the war, not the Hiroshima bomb, that convinced the Japanese leadership to surrender." Some argue that the United States also aimed to demonstrate the atomic bomb’s destructive power to the Soviet Union, seeking to establish a position of strength in the postwar world and influence the emerging global power dynamics that eventually led to the Cold War.

For the survivors, the hibakusha (被爆者, translating to person affected by the atomic bombing), these reasons, as important as they are, serve to mask the human tragedy at the heart of Hiroshima. Keiji Nakazawa, one survivor who went on to become a manga artist, wrote:

"The atomic bomb was not just a weapon. It was hell on earth."

Children were burned alive on their way to school; mothers searched for their sons among the ruins of buildings; survivors were disfigured, afflicted with disease, and socially ostracised for centuries. Their testimonies are an eyewitness moral record. Setsuko Thurlow, who survived to become a leading voice on nuclear disarmament, reported in her Nobel Peace Prize address (2017):

"Each person had a name. Each person was somebody's loved one. Let us ensure their deaths did not go in vain.”

Hiroshima marks a turning point since it revolutionised world politics. The arrival of the nuclear age meant man now had the ability to annihilate itself. The Soviet Union already tested its bomb within four years of Hiroshima, and an arms race broke out, which defined the Cold War. By the 1960s, the world was living in the shadow of "mutually assured destruction" (MAD), a paradoxical policy by which peace was ensured only through the spectre of utter destruction. The hibakusha, though, became symbols not only of victimhood but of resistance against nuclear weapons proliferation. They reminded the world that nuclear weapons are not theoretical deterrents but real instruments of human suffering.

Just over 80 years later, Hiroshima is still relevant today. The US and Russia still possess 87% of the world's nuclear warheads, despite four decades of disarmament talks (such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT)). Although it is a gradual process, efforts to restrict or outlaw nuclear weapons have been made with the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty and the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. For national security and deterrence reasons, other nuclear-armed nations like the US, Russia, China, and India have declined to sign legally binding disarmament treaties. UN Secretary-General António Guterres issued a concerning warning in 2023:

"Humanity is just one misunderstanding, one miscalculation, away from nuclear annihilation."

Global tensions give this warning an air of immediacy. Russian nuclear bluffs during the war in Ukraine, current North Korean weapons tests, and greater competition in the South China Sea have brought renewed fear of nuclear war to the modern day. Hiroshima is not just a 1945 memory but an echo of our vulnerabilities. The danger is perhaps even larger today since more and more countries possess nuclear weapons, and non-state actors have reignited the specter of nuclear terrorism.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, an annual ritual at Peace Memorial Park, remains an exercise in mourning and defiance. At 8:15 a.m., the city holds its breath; paper lanterns float along the Motoyasu River, carrying the names of the dead. These are not merely exercises in mourning but exercises in protest against complacency. But as historian John Dower has pointed out, "humanity remembers, but does not always learn." Nuclear powers continue to enhance their arsenals with hypersonic missiles and tactical warheads, even though hibakusha are demanding full disarmament.

The lessons of Hiroshima are therefore twofold. They initially depict the horrific human cost of nuclear war — not a hypothetical strategy, but death, broken families, and poisoned habitats. They also serve to demonstrate the bounds of political resolve when security and authority are the primary concerns on the global agenda. Recalling Hiroshima forces us to confront a central paradox: is deterrence through nuclear weapons truly a promise of peace, or simply a frenzied wager on humankind's continued existence?

For those of us alive today, the urgency of the issue is real: the experience of global warming, pandemic disease, and cyberwars have already pushed the limits of international stability; nuclear war would be an unparalleled disaster. To remember Hiroshima is to set aside space to memorialise the victims of Hiroshima and to face the reality of our world today: nuclear arms still exist, the threat is still great, and we need to take action to ensure that there is no second Hiroshima.

Ultimately, August 6 is not so much about the past. It is a call to governments to approach disarmament in good faith, a challenge to societies to abandon the nuclear weaponisation of normal life, and a challenge to young people to leave behind the hibakusha's testament as a warning and guide. Hiroshima remains man's worst moment — and our finest test of conscience: whether we can learn from the horror to make a less dangerous, more peaceful world.

“I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones” - Einstein

Bibliography

Comments